The Photograph that Allowed Geniuses to Have a Sense of Humor

THE PHOTOS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

1.

2.

3.

- Read the stories about the photos.

1.

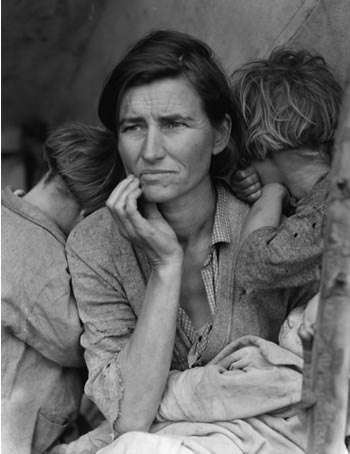

The Photograph That Gave a Face to the Great Depression

"Migrant Mother"

Dorothea Lange, 1936

As era-defining photographs go, "Migrant Mother" pretty much takes the cake. For many, Florence Owens Thompson is the face of the Great Depression, thanks to legendary shutterbug Dorothea Lange. Lange captured the image while visiting a dusty California pea-pickers’ camp in February 1936, and in doing so, captured the resilience of a proud nation facing desperate times.

Unbelievably, Thompson’s story is as compelling as her portrait. Just 32 years old when Lange approached her (“as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange said). Thompson was a mother of seven who had lost her husband to tuberculosis. Stranded at a migratory labor farm in Nipomo, California, her family sustained themselves on birds killed by her kids and vegetables taken from a nearby field – as meager a living as any earned by the other 2,500 workers there. The photo’s impact was staggering. Reproduced in newspapers everywhere, Thompson’s haunted face triggered an immediate public outcry, quickly prompting politicos from the federal Resettlement Administration to send food and supplies.

2.

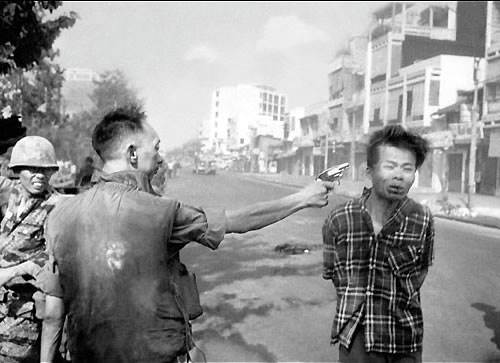

The Photograph That Ended a War But Ruined a Life

"Murder of a Vietcong by Saigon Police Chief"

Eddie Adams, 1968

“Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world,” AP photojournalist Eddie Adams once wrote. A fitting quote for Adams, because his 1968 photograph of an officer shooting a handcuffed prisoner in the head at point-blank range not only earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1969, but also went a long way toward souring Americans’ attitudes about the Vietnam War.

For all the image’s political impact, though, the situation wasn’t as black-and-white as it’s rendered. What Adams’ photograph doesn’t reveal is that the man being shot was the captain of a Vietcong “revenge squad” that had executed dozens of unarmed civilians earlier the same day. Regardless, it instantly became an icon of the war’s savagery and made the official pulling the trigger – General Nguyen Ngoc Loan – its iconic villain.

Sadly, the photograph’s legacy would haunt Loan for the rest of his life. Following the war, he was reviled wherever he went. After an Australian VA hospital refused to treat him, he was transferred to the United States, where he was met with a massive (though unsuccessful) campaign to deport him. He eventually settled in Virginia and opened a restaurant but was forced to close it down as soon as his past caught up with him. Vandals scrawled “we know who you are” on his walls, and business dried up.

Adams felt so bad for Loan that he apologized for having taken the photo at all, admitting, “The general killed the Vietcong; I killed the general with my camera.”

3.

The Photograph that Allowed Geniuses to Have a Sense of Humor

"Einstein with his Tongue Out"

Arthur Sasse, 1951

You may appreciate this memorable portrait, but it’s still fair to wonder: “Did it really change history?” We think it did. While Einstein certainly changed history with his contributions to nuclear physics and quantum mechanics, this photo changed the way history looked at Einstein. By humanizing a man known chiefly for his brilliance, this image is the reason Einstein’s name has become synonymous not only with "genius," but also with "wacky genius."

So why the history-making tongue? It seems Professor Einstein, hoping to enjoy his 72nd birthday in peace, was stuck on the Princeton campus enduring incessant hounding by the press. Upon being prodded to smile for the camera for what seemed like the millionth time, he gave photographer Arthur Sasse a good look at his tongue instead. This being no ordinary tongue, the resulting photo became an instant classic, thus ensuring that the distinguished Novel Prize-winner would be remembered as much for his personality as for his brain.

- Answer the following questions

1. Which story impressed you most of all? Why?

2. Do you think that all the photos are equally important? What makes you think so?

3. If you had a chance to interview Dorothea Lange, Arthur Sasse or Eddie Adams – whom would you interview? Why? What questions would you ask?

4. Role-play an interview (a press-conference) with one of the photographers.

Reading

- Before you read

ü Look at the picture

ü Would you buy a biography called Blood and Champagne? What kind of person would inspire such a book?

ü Whom would you call an ideal photo correspondent? Why? List the features such a person should possess. Compare your lists.

Robert Capa, in Focus

Robert Capa, the legendary Hungarian-born photojournalist who set the prevailing standard for war photographers, spoke seven languages — none very well. He didn't need to. For over 20 of the bloodiest years of the 20th century, Capa let his cameras do the talking. “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” he famously declared.

Getting close to Capa himself could also be a tricky business, though the challenge was usually surmounted by soldiers, poker players, bartenders, writers, artists and beautiful women. Nearly a half-century after Capa’s untimely death while covering the French colonial war in Indochina – and after four years of dogged research – the British journalist and author Alex Kershaw has also gotten close. In his elegant Capa biography, Blood and Champagne, Kershaw portrays an indisputably brave and talented photographer who could also be reckless, cynical and opportunistic. Much as Capa held his camera only inches from the faces of the grief-stricken and the grievously wounded, Kershaw focuses – tightly and unblinkingly – on a man who “invented himself” and who was exposed to an excess of both joy and horror in his 41 years.

Born André Friedmann in Budapest in 1913, Capa entered a world in conflict, between nations and between his parents. In his teens, André – poor, clever, bored, romantic at heart and discriminated against as a Jew – became involved with leftist revolutionaries, seeking out conflict and danger. When he was barely 18, he moved to Berlin and took up photojournalism. His first big break came in 1932, when he was assigned to photograph Trotsky as he spoke in a Copenhagen stadium on the meaning of the Russian Revolution. His pictures were the most dramatic of the day, writes Kershaw. Taken within a meter of so of Trotsky, they were intense, intimate and imperfect – the trademarks of the man who would become famous as Capa, or “shark” in Hungarian.

As Nazi power grew in Germany, Friedmann moved to Paris, the only city he would ever consider home. In France, he documented the social and industrial strife of the mid-1930s, struggled to earn a living and fell in love with Gerda Taro. Accepting him for what he was – a charming rogue, a heavy drinker and a notorious womanizer – Taro shared his work, his life and his dreams. Together they invented Robert Capa, a rich, famous, talented American photographer whose name on a picture boosted its price. In 1936, they moved on to war-torn Spain, determined to fight totalitarianism with cameras. The following year, Taro was killed there, in a road accident. Capa was inconsolable, and part of him died with her. Still, he pursued his calling, traveling to China in 1938 to cover the Sino-Japanese war, back to Spain as the Republican cause was collapsing and then, as World War II raged, on to North Africa, Sicily, the Italian mainland and – most traumatically – to Omaha Beach and the slaughter of the D-Day invasion. It was in Spain that Capa took his best-known photo, which purported to show a militiaman a split second after he’d been fatally shot. Debate over its authenticity still rages. The “truth” of the photo, says Kershaw, is in its representation of a symbolic death. “The Falling Soldier, authentic or fake, is ultimately a record of Capa’s political bias and idealism,” he writes, adding: “Indeed, he would soon come to experience the brutalizing insanity and death of illusions that all witnesses who get close enough to the ‘romance’ of war inevitably confront.”

In 1946, after more than a decade of front-line reporting, says Kershaw, “Capa had started to exhibit many of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder: restlessness, heavy drinking, irritability, depression, survivor’s guilt, lack of direction and barely concealed nihilism.” He fulfilled a dream in 1947, though, by setting up the Magnum photo cooperative, named after the large champagne bottle. Capa next traveled to the Soviet Union, but the cold war did not suit his talents. Grazed – and badly shaken – by a bullet in Tel Aviv in 1948, he sat out the Korean War. But the gambler in him was lured back into the fray in 1954, to work again for Life magazine.

“This is going to be a beautiful story,” he said as he set out from the village of Nam Dinh, in Vietnam's Red River delta, on May 25, the last morning of his life. “I will be on my good behavior today. I will not insult my colleagues, and I will not once mention the excellence of my work.” Eight hours – and 30 km – later, Capa was dead, killed by a landmine, as he tried to get just that little bit closer.

By Maryann Bird

(Time)

(Capa’s most famous photo)

Having read the text

ü Look at your lists of qualities important for a photo correspondent. Did Robert Capa possess any of them?

ü What important points in his career does the author mention?

ü What sort of personality does he describe? Would you call Robert Capa an amiable person?

· Choose the variant that fits best according to the text

1. Saying that Capa set prevailing standard for war photographers, the author means that he set

A. a very high standard

B. the widespread standard

C. the unique standard

2. Saying that ‘getting close to Capa himself could also be a tricky business’, the author means that

A. it was dangerous to get in touch with Capa

B. Capa was surrounded by specific people

C. Capa was fond of playing tricks on people

3. Saying that Kershaw in his book portrays an indisputably brave photographer, the author means that

A. there were no doubts that Capa was brave

B. there were some disputes about his bravery

C. no one has ever disputed the fact that Capa was brave

4. Saying that Capa could be reckless,the author means that

A. he did not care about the consequences of his actions

B. he was a very brave person

C. he was not a very smart person

5. Saying that Capa’s photos were intense, intimate and imperfect, the author means that

A. the photos were good

B. the photos were bad

C. the photos were unique

6. Calling Capa a rogue the author means that

A. he behaved in an unpredictable way

B. he was a criminal

C. he was a dishonest man

7. Saying that Capa and his wife were determined to fight totalitarianism with cameras, the author means that

A. they had a firm decision to take part in the war against totalitarianism

B. they took part in the civil war in Spain

C. they had a firm decision to do what they could to help those who fought against totalitarianism

8. Saying that Capa pursued his calling, the author means that he

A. travelled a lot

B. did not drop photography

C. had a hobby which was very important for him

9. Saying that Capa’s best-known photo purported to show a militiaman a split second after he’d been fatally shot, the author means that

A. this photo showed a dying soldier

B. this photo showed a soldier who was fatally shot

C. he is not sure that this photo shows a militiaman a split second after he’d been fatally shot

10. Saying that Capa was lured back into the fray, the author means that

A. Capa turned back to the work of photo correspondent

B. Capa went to the warfare once again

C. Capa wanted to tale part in a fray