WHY BRITISH SINGERS LOSE THEIR ACCENTS WHEN SINGING

Текст 4

IMPOLITENESS IN INTERPRETING: A QUESTION OF GENDER?

(http://www.trans-int.org/index.php/transint/article/view/532/253)

Conclusion

This paper aimed at examining the interpreters’ handling of face-threatening acts in the community of practice consisting of EP (European Parliament) interpreters. Based on earlier research in interpreting studies and sociolinguistics, two research Translation & Interpreting Vol 8 No 2 (2016) 43 questions were asked: (1) do interpreters attend to the face needs of the interlocutors and will they therefore engage in face work while interpreting FTAs? (2) Is there a gender bias in handling FTAs, as women were found in spontaneous speech context to use fewer FTAs? Or does the community of practice EP interpreters belong to smooth out gender differences?

The corpus data available for this study allow us to answer the first question affirmatively. Interpreters indeed alter or even omit FTAs, especially when these are not mitigated by the speakers themselves. Regarding alterations, downtoning of FTAs is four times as frequent as strengthening, which is clear evidence of the fact that interpreters seek to save face. As pointed out, omissions are not necessarily signs of face work, but the fact that they occur more often in the case of unmitigated FTAs than in the case of FTAs mitigated by the speakers, seems to suggest that they are also used by the interpreters as face-saving strategies. Further research on this topic, such as the study of face-boosting mechanisms or face-enhancing acts could give a better insight in this field.

The results relating to the second question were more surprising: it turned out that female interpreters downtone fewer FTAs than do their male counterparts. A closer analysis revealed that male interpreters downtone a majority of the unmitigated FTAs they perceive. Face-saving thus appears to be primarily a male strategy. In other words, the EU interpreter community of practice appeared to be gendered. It also shows cultural bias to a certain extent, as booths do not downtone to the same degree. These results spark new research questions that could lead to new insights in gender differences in interpreting: are female interpreters less concerned with face-saving because it infringes professional norms that they deem more important than the face needs of the interlocutors? Is face-saving determined by the gender of the speaker, and, more particularly, the gender combination of speaker and interpreter? Shifting the focus from sociolinguistic determinants to professional determinants will enable us to answer these questions.

Текст 5

WHY BRITISH SINGERS LOSE THEIR ACCENTS WHEN SINGING

August 9, 2013 Deborah Honeycutt Comments

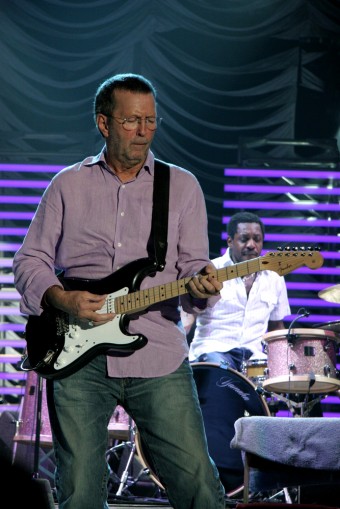

Mick Jagger, Elton John, Rod Stewart, Ed Sheeran, Phil Collins and George Michael all grew up in or near London and have very recognizably British accents. Once on stage, they sing like someone who grew up in New England rather than old. Yet another example is Adele, who has a lovely speaking voice, a very heavy cockney accent, yet her singing pipes do not indicate her dialect. One might argue that Adele’s speaking and singing voices were two different people if listening without visuals. Going beyond the British, we see the same thing with other non-American musicians, such as the Swedish band ABBA, and many others singing in English, yet from various places around the world. It seems like no matter where you’re from, if you’re singing in English, you’re probably singing with an American accent, unless you’re actively trying to retain your native accent, which some groups do.

There are several reasons we notice accents ‘disappearing’ in song, and why those singing accents seem to default to “American”. In a nutshell, it has a lot to do with phonetics, the pace at which they sing and speak, and the air pressure from one’s vocal chords. As far as why “American” and not some other accent, it’s simply because the generic “American” accent is fairly neutral. Even American singers, if they have, for instance, a strong “New Yorker” or perhaps a “Hillbilly” accent, will also tend to lose their specific accent, gravitating more towards neutral English, unless they are actively trying not to, as many Country singers might.

For the specific details, we’ll turn to linguist and author, David Crystal, from Northern Ireland. According to Crystal, a song’s melody cancels out the intonations of speech, followed by the beat of the music cancelling out the rhythm of speech. Once this takes place, singers are forced to stress syllables as they are accented in the music, which forces singers to elongate their vowels. Singers who speak with an accent, but sing it without, aren’t trying to throw their voice to be deceptive or to appeal to a different market; they are simply singing in a way that naturally comes easiest, which happens to be a more neutral way of speaking, which also just so happens to be the core of what many people consider an “American” accent.

To put it in another way, it’s the pace of the music that affects the pace of the singer’s delivery. A person’s accent is easily detectable when they are speaking at normal speed. When singing, the pace is often slower. Words are drawn out and more powerfully pronounced and the accent becomes more neutral.

Another factor is that the air pressure we use to make sounds is much greater when we sing. Those who sing have to learn to breathe correctly to sustain notes for the right amount of time, and singing requires the air passages to expand and become larger. This changes the quality of the sound. As a result, regional accents can disappear because syllables are stretched out and stresses fall differently than in normal speech. So, once again, this all adds up to singing accents becoming more neutral.