UNDERSTANDING DATA, INFORMATION, KNOWLEDGE AND THEIR INTERRELATIONSHIPS

Г. Д. Малик

М. В. Кісіль

Information Challenges

хрестоматія

Івано-Франківськ

«Прінт-СВ»

УДК 811.111 (075.8)

ББК Ч 481.268 + Ш 143 я 73

М - 19

| Рецензенти: | Богачевська Лілія Орестівна, доцент кафедри іноземних мов та перекладу Прикарпатський національний університет, м. Івано-Франківськ |

| Назаренко Наталія Степанівна, доцент кафедри перекладу, Національна академія Державної прикордонної служби України імені Богдана Хмельницького, м. Хмельницький |

Рекомендовано до видання кафедрою теорії та практики перекладу (протокол № 3 від 19.09.2012) та кафедрою документознавства та інформаційної діяльності Івано-Франківського національного технічного університету нафти і газу.

| М-19 | Малик Г. Д., Кісіль М. В. Information Challenges: хрестоматія |

| – Івано-Франківськ: Фоліант, 2012. – 119 с. | |

| Призначені для студентів спеціальностей “Переклад” та “Документознавство та інформаційна діяльність” |

| УДК 811.111 (075.8) ББК Ч 481.268 + Ш 143 я 73 | © Г. Д. Малик, М. В. Кісіль, 2013 © ІФНТУНГ, 2013 |

CONTENTS

| TOPIC 1 | INFORMATION AGE | |

| Text 1 | Understanding Data, Information, Knowledge and Their Interrelationships....... | |

| Text 2 | How to Build Wisdom and Prosper in an Information Age? ….......................... | |

| Text 3 | 5 Myths about the Information Age…................................................................. | |

| Text 4 | Brief Overview of Document Management......................................................... | |

| Text 5 | Understanding Documents and Documentation................................................... | |

| Text 6 | The Transformation of Document Storage into Records Management............... | |

| Text 7 | Problems and Challenges of the Information Age…........................................... | |

| Text 8 | Hidden-Information Agency…............................................................................ | |

| TOPIC 2 | Information professionals | |

| Text 1 | The Role of Information Professionals in Global Economic Crisis…................ | |

| Text 2 | Entrepreneurship Education and Information Professionals…........................... | |

| Text 3 | Information Professionals in the Information Age: Vital Skills and Competencies…................................................................................................... | |

| Text 4 | The Information Professional facing the impact of Search Technology............. | |

| Text 5 | The Changing Role of the Information Professional........................................... | |

| Text 6 | Challenges in Educating 21st-Century Information Professionals....................... | |

| Text 7 | Information Professionals in the Corporate World.............................................. | |

| Text 8 | The Future of the Information Professional........................................................ | |

| TOPIC 3 | MASS MEDIA | |

| Text 1 | The Freedom of Expression and Information.................................................... | |

| Text 2 | Mass Media and its Influence on Society........................................................... | |

| Text 3 | Pros and Cons of Mass Media............................................................................ | |

| Text 4 | Seven Myths About Media Effects..................................................................... | |

| Text 5 | Children and the Media........................................................................................ | |

| Text 6 | Ten Reasons to Advertise in a Newspaper......................................................... | |

| Text 7 | E-newspapers: Revolution or Evolution?............................................................ | |

| Text 8 | Are Newspapers Dying? Yes or No? ................................................................. | |

| TOPIC 4 | INTERNET | |

| Text 1 | Internet as an important element of the information society and e-business development......................................................................................................... | |

| Text 2 | The Internet Revolution: It came. It went. It's here ……………………………. | |

| Text 3 | Consumer Benefit from Use of the Internet …………………………………… | |

| Text 4 | The Educational Advantages of Using Internet…………………………........... | |

| Text 5 | From Media Literacy to Digital Skills................................................................. | |

| Text 6 | Social Network Sites............................................................................................ | |

| Text 7 | History of E-books………………....………………………………………….. | |

| Text 8 | The future of the Internet is wired into the human brain..................................... | |

| TOPIC 5 | censorship | |

| Text 1 | Censorship, Violence & Press Freedom.............................................................. | |

| Text 2 | Censoring and Destroying Information in the Information.................................. | |

| Text 3 | Pros and Cons of Censorship .............................................................................. | |

| Text 4 | Media Censorship: Why is Censorship Good .................................................... | |

| Text 5 | Censorship and the Arts ..................................................................................... | |

| Text 6 | Data Driven Futures - Censorship Takes New Forms........................................ | |

| Text 7 | Kids' Book Censorship: The Who and Why....................................................... | |

| Text 8 | Why Not Censor? ................................................................................................ | |

| TOPIC 6 | PUBLIC RELATIONS | |

| Text 1 | A Brief History of PR........................................................................................ | |

| Text 2 | The Important Role of Public Relations............................................................... | |

| Text 3 | 10 Principles of Public Relations......................................................................... | |

| Text 4 | Ethical Public Relations: Not an Oxymoron....................................................... | |

| Text 5 | PR Across Cultures: Building International Communication Bridges................ | |

| Text 6 | PR and Blogging – How to Think about It?....................................................... | |

| Text 7 | How to Choose Between PR and Advertising..................................................... | |

| Text 8 | How to Run Ethically Sound PR Campaigns....................................................... | |

| TOPIC 7 | NEGOTIATION | |

| Text 1 | Deal or No Deal? Resolving Conflict through Negotiation ............................. | |

| Text 2 | Importance of Good Communication Skills in Negotiation…............................ | |

| Text 3 | A Buyers’ and Sellers’ Guide to Multiple Offer Negotiations............................ | |

| Text 4 | Deception in Negotiations: The Role of Emotions ………………………......... | |

| Text 5 | Differences in Business Negotiations between Different …............................... | |

| Text 6 | Negotiation Conflict Styles.................................................................................. | |

| Text 7 | Win-Win Negotiations........................................................................................ | |

| Text 8 | Ten Tips for Negotiating in 2013......................................................................... |

Information Age

Text 1

UNDERSTANDING DATA, INFORMATION, KNOWLEDGE AND THEIR INTERRELATIONSHIPS

By Anthony Liew[1]

Despite many attempts at the definition of ‘Data’, ‘Information’, and ‘Knowledge’, there still seems to be a lack of a clear and complete picture of what they are and the relationships between them. Although many definitions are relevant, they are far from being complete. It is not the intention of this paper to criticize those whom have paved the way to better understanding of the topic. Rather, the goal is to provide a different or new perspective in the context of business and knowledge management.

Data are recorded (captured and stored) symbols and signal readings. Symbols include words (text and/or verbal), numbers, diagrams, and images (still &/or video), which are the building blocks of communication. Signals include sensor and/or sensory readings of light, sound, smell, taste, and touch.

As symbols, ‘Data’ is the storage of intrinsic meaning, a mere representation. The main purpose of data is to record activities or situations, to attempt to capture the true picture or real event. Therefore, all data are historical, unless used for illustration purposes, such as forecasting.

Information is a message that contains relevant meaning, implication, or input for decision and/or action. Information comes from both current (communication) and historical (processed data or ‘reconstructed picture’) sources. In essence, the purpose of information is to aid in making decisions and/or solving problems or realizing an opportunity.

Knowledge is the cognition or recognition (know-what), capacity to act (know-how), and understanding (know-why) that resides or is contained within the mind or in the brain. The purpose of knowledge is to better our lives. In the context of business, the purpose of knowledge is to create or increase value for the enterprise and all its stakeholders. In short, the ultimate purpose of knowledge is for value creation.

Given the definitions for data, information, and knowledge, the relationships between data and information, information and knowledge, why they are most often regarded as interchangeable and when they are not, the processes and their relevance to our intended application can be explored. The key to understanding the intricate relationship between data, information, and knowledge lies at the source of data and information. The source of both is twofold: activities, and situations. Both activities and situations generate information (i.e. ‘relevant meaning’ to someone) that either is captured thus becoming Data, or becomes oblivious (lost).

Assignments

1. Give a definition of data according to this article.

2. What do symbols include?

3. What do signals include?

4. Explain what information is according to the author of this paper.

5. What is the difference between data and information?

6. What is the purpose of information?

7. What sources does information come from? The figure below may be helpful.

Fig. 1.1 Types of information sources

8. What is knowledge?

9. What is the purpose of knowledge in the context of business?

10. Summarize the text.

Text 2

HOW TO BUILD WISDOM AND PROSPER IN AN ‘INFORMATION AGE’

By A. J. Schuler[2]

You always hear it said that we live in an “information age.” But what does that mean, and how should we understand the challenges of the so-called “information age?” More importantly, given that we are all flooded with more information that we can possibly process (have you ever wanted to run screaming from your television, radio or email box?), how can you turn the special circumstances of this “information age” to your advantage? You’ll have to climb the “Wisdom Ladder.” Here’s how:

Bottom Step on the Wisdom Ladder: Data

“Data” means raw counts of things. Data can be useful or not useful. In and of itself, data has no meaning. If I count the number of cars that stop at the stop sign on my block per hour for a week, that’s data. It may be useful or not, depending on the context. It has no meaning until it is placed in a context. Data can be accurate or inaccurate. It can also be reliable or unreliable, valid or invalid. What’s the difference? Imagine a target at which I shoot arrows using some machine. If I shoot ten arrows and they all cluster around one spot in the lower left corner of the target, I have a reliable machine, but not a very accurate (“valid”) one. If I shoot ten arrows that scatter all over the target, but whose hit points all average out to the middle, I have a pretty accurate (“valid”) machine, but it’s not very reliable. When we collect data, we want to use instruments that are both reliable (they get consistent results within a reasonable spread of error) and valid (they really measure what we intend them to measure). The differences are subtle, but important for anyone who collects - and seeks to interpret - data. Data is only as good as the measurement device we use to collect it: and if I fall asleep watching my street corner, I’m not a very good data collector!

Second Step on the Wisdom Ladder: Information

When you put a whole lot of data together that is related toone subject, it can be collected to yield information. In other words, (sets of data) + (collection of related data sets) = information. Let’s say I want to buy a car. I can collect a lot of data about makes of cars, performance ratings, prices and so on. Once I do that, I have a lot of information about cars and the auto market. Until I think about this collection of data - this information - and put it in context, it is “dumb.” By that I mean it has no meaning. This is what we are flooded with every day. On the Internet, we can find lots and lots of information - dumb collections of data. Some of that information may be useful, and some of it may be accurate. But living in an “information age” means we are flooded all the time with access to more information than we can possibly have time to put in context. We don’t have time to decide what it means, and it comes at us so fast! The amount of information available to anyone in the world today is absolutely staggering, given historical standards. It is truly, lierally mind-boggling.

Third Step on the Wisdom Ladder: Knowledge

Once you spend some time interpreting and understanding a body of information, then you have knowledge. This takes time. While technology has greatly reduced the cost involved in assembling and storing data, and in transferring and storing information, technology has not done anything to make the process of creating knowledge any quicker or cheaper. Creating knowledge still takes brains, thought and time - especially today when there is so much more information available to wade through. People can become knowledge experts for a given subject, which, in an “information age,”means they really are just advanced, perpetual students for that given subject. We rely on these people to help us bypass the costly process of wading through large bodies of information ourselves. As a result, the credibility of knowledge experts is that much more important (and often hard to assess). On the one hand, we have to be able to trust them to give us honest, valid and reliable knowledge, and on the other, we lack the subject specific knowledge to know whether or not they are really as reliable and credible as we need them to be. It’s a catch-22: if we had the knowledge with which to judge them, we would not need them in the first place! So what’s the solution?

Top Step on the Wisdom Ladder: Wisdom

Wisdom is precious - and worth paying for. It comes from the ability to synthesize various streams of knowledge - even seemingly unrelated bodies of knowledge - enough to be able to make informed judgments about various ideas and propositions that may lie outside of our own direct areas of expertise. Certain patterns in nature repeat themselves, no matter where they may be found. Wisdom entails having enough experience and perspective to spot such patterns and trends so that various bodies of knowledge can be put in context, combined and applied appropriately. Inevitably, wisdom requires a deep, perhaps intuitive understanding of human nature - of ambition, styles of intelligence, human motivations, etc. - enough to allow the possessor of wisdom to make judgments about representations of knowledge that lie outside of his or her own expertise. This is how we can escape from the dilemma of the need to make judgments about experts who posses bodies of knowledge that we lack. Wisdom amounts to something more than “street smarts,” but the sharpness of judgment implied by the phrase “street smarts” is encompassed by wisdom.

Your grandparents may perhaps have been short on book smarts (“knowledge”) but long on wisdom. In an “information age,” technology cannot confer wisdom: wisdom takes more time to develop and cultivate than even knowledge does (how many people do you know with advanced degrees who lack wisdom or wise judgment?). For this reason, wisdom is at an even higher premium, perhaps, than it has ever been, and when you find a good, credible source of wisdom (a person) who can help you make good judgments and grow your own store of wisdom, that’s a relationship to build and hold firm. This is why really good mentoring is so valuable, and why the most effective executives and leaders are extremely adept at understanding other people. Wisdom combines the seasoned experience of connecting and reviewing bodies of knowledge, together with a genuine grasp of human nature and the ways of the world, to allow for the proper use of data, information and knowledge. Wise people, therefore, cultivate connections with other wise people or reliable knowledge experts, because this is the most effective way to leverage and benefit from vast stores of knowledge in this “information age.”

Assignments

1. What is the difference in terms of information presented in this text and the previous one?

2. What does the term “data” mean?

3. Explain the following statement: “Data may be useful or not depending on the context”.

4. Compare knowledge and wisdom.

5. Why is wisdom precious and worth paying for?

6. Why cannot technology confer wisdom in an information age?

7. Are the following statements true or false?

· Data is a set of discrete facts. Most organizations capture significant amounts of data in highly structured databases such as service management and service asset and configuration management tools/systems and databases. An example of data is the incident log entry with date and time.

· Information comes from providing context to data. Information is typically stored in semi-structured content such as documents, email and multimedia.

· Knowledge is composed of the tacit experiences, ideas, insights, values and judgments of individuals.

· Wisdom makes use of knowledge to create value through correct and well-informed decisions.

8. Comment on the following statement:

· The amount of information available to anyone in the world today is absolutely staggering, given historical standards. It is truly, lierally mind-boggling.

9. Describe the main steps on the WisdomLadder using the figure below.

Fig. 1.2 Wisdom Ladder

10. Summarize the text

Text 3

5 Myths About the 'Information Age'

By Robert Darnton[3]

Confusion about the nature of the so-called information age has led to a state of collective false consciousness. It's no one's fault but everyone's problem, because in trying to get our bearings in cyberspace, we often get things wrong, and the misconceptions spread so rapidly that they go unchallenged. Taken together, they constitute a font of proverbial nonwisdom. Five stand out:

1. "The book is dead." Wrong: More books are produced in print each year than in the previous year. One million new titles will appear worldwide in 2011. In one day in Britain—"Super Thursday," last October 1—800 new works were published. The latest figures for the United States cover only 2009, and they do not distinguish between new books and new editions of old books. But the total number, 288,355, suggests a healthy market, and the growth in 2010 and 2011 is likely to be much greater. Moreover, these figures, furnished by Bowker, do not include the explosion in the output of "nontraditional" books—a further 764,448 titles produced by self-publishing authors and "micro-niche" print-on-demand enterprises. And the book business is booming in developing countries like China and Brazil. However it is measured, the population of books is increasing, not decreasing, and certainly not dying.

2. "We have entered the information age." This announcement is usually intoned solemnly, as if information did not exist in other ages. But every age is an age of information, each in its own way and according to the media available at the time. No one would deny that the modes of communication are changing rapidly, perhaps as rapidly as in Gutenberg's day, but it is misleading to construe that change as unprecedented.

3. "All information is now available online." The absurdity of this claim is obvious to anyone who has ever done research in archives. Only a tiny fraction of archival material has ever been read, much less digitized. Most judicial decisions and legislation, both state and federal, have never appeared on the Web. The vast output of regulations and reports by public bodies remains largely inaccessible to the citizens it affects. Google estimates that 129,864,880 different books exist in the world, and it claims to have digitized 15 million of them—or about 12 percent. How will it close the gap while production continues to expand at a rate of a million new works a year? And how will information in nonprint formats make it online en masse? Half of all films made before 1940 have vanished. What percentage of current audiovisual material will survive, even in just a fleeting appearance on the Web? Despite the efforts to preserve the millions of messages exchanged by means of blogs, e-mail, and handheld devices, most of the daily flow of information disappears. Digital texts degrade far more easily than words printed on paper. Brewster Kahle, creator of the Internet Archive, calculated in 1997 that the average life of a URL was 44 days. Not only does most information not appear online, but most of the information that once did appear has probably been lost.

4. "Libraries are obsolete." Everywhere in the country librarians report that they have never had so many patrons. At Harvard, our reading rooms are full. The 85 branch libraries of the New York Public Library system are crammed with people. The libraries supply books, videos, and other material as always, but they also are fulfilling new functions: access to information for small businesses, help with homework and afterschool activities for children, and employment information for job seekers (the disappearance of want ads in printed newspapers makes the library's online services crucial for the unemployed). Librarians are responding to the needs of their patrons in many new ways, notably by guiding them through the wilderness of cyberspace to relevant and reliable digital material. Libraries never were warehouses of books. While continuing to provide books in the future, they will function as nerve centers for communicating digitized information at the neighborhood level as well as on college campuses.

5. "The future is digital." True enough, but misleading. In 10, 20, or 50 years, the information environment will be overwhelmingly digital, but the prevalence of electronic communication does not mean that printed material will cease to be important. Research in the relatively new discipline of book history has demonstrated that new modes of communication do not displace old ones, at least not in the short run. Manuscript publishing actually expanded after Gutenberg and continued to thrive for the next three centuries. Radio did not destroy the newspaper; television did not kill radio; and the Internet did not make TV extinct. In each case, the information environment became richer and more complex. That is what we are experiencing in this crucial phase of transition to a dominantly digital ecology.

I mention these misconceptions because I think they stand in the way of understanding shifts in the information environment. They make the changes appear too dramatic. They present things ahistorically and in sharp contrasts—before and after, either/or, black and white. A more nuanced view would reject the common notion that old books and e-books occupy opposite and antagonistic extremes on a technological spectrum. Old books and e-books should be thought of as allies, not enemies. To illustrate this argument, I would like to make some brief observations about the book trade, reading, and writing.

Last year the sale of e-books (digitized texts designed for hand-held readers) doubled, accounting for 10 percent of sales in the trade-book market. This year they are expected to reach 15 or even 20 percent. But there are indications that the sale of printed books has increased at the same time. The enthusiasm for e-books may have stimulated reading in general, and the market as a whole seems to be expanding. New book machines, which operate like ATM's, have reinforced this tendency. A customer enters a bookstore and orders a digitized text from a computer. The text is downloaded in the book machine, printed, and delivered as a paperback within four minutes. This version of print-on-demand shows how the old-fashioned printed codex can gain new life with the adaption of electronic technology.

Many of us worry about a decline in deep, reflective, cover-to-cover reading. We deplore the shift to blogs, snippets, and tweets. In the case of research, we might concede that word searches have advantages, but we refuse to believe that they can lead to the kind of understanding that comes with the continuous study of an entire book. Is it true, however, that deep reading has declined, or even that it always prevailed? Studies by Kevin Sharpe, Lisa Jardine, and Anthony Grafton have proven that humanists in the 16th and 17th centuries often read discontinuously, searching for passages that could be used in the cut and thrust of rhetorical battles at court, or for nuggets of wisdom that could be copied into commonplace books and consulted out of context.

In studies of culture among the common people, Richard Hoggart and Michel de Certeau have emphasized the positive aspect of reading intermittently and in small doses. Ordinary readers, as they understand them, appropriate books (including chapbooks and Harlequin romances) in their own ways, investing them with meaning that makes sense by their own lights. Far from being passive, such readers, according to de Certeau, act as "poachers," snatching significance from whatever comes to hand.

Writing looks as bad as reading to those who see nothing but decline in the advent of the Internet. As one lament puts it: Books used to be written for the general reader; now they are written by the general reader. The Internet certainly has stimulated self-publishing, but why should that be deplored? Many writers with important things to say had not been able to break into print, and anyone who finds little value in their work can ignore it.

The online version of the vanity press may contribute to the information overload, but professional publishers will provide relief from that problem by continuing to do what they always have done—selecting, editing, designing, and marketing the best works. They will have to adapt their skills to the Internet, but they are already doing so, and they can take advantage of the new possibilities offered by the new technology.

To use an an example from my own experience, I recently wrote a printed book with an electronic supplement, Poetry and the Police: Communication Networks in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Harvard University Press). It describes how street songs mobilized public opinion in a largely illiterate society. Every day, Parisians improvised new words to old tunes, and the songs flew through the air with such force that they precipitated a political crisis in 1749. But how did their melodies inflect their meaning? After locating the musical annotations of a dozen songs, I asked a cabaret artist, H?l?ne Delavault, to record them for the electronic supplement. The reader can therefore study the text of the songs in the book while listening to them online. The e-ingredient of an old-fashioned codex makes it possible to explore a new dimension of the past by capturing its sounds.

One could cite other examples of how the new technology is reinforcing old modes of communication rather than undermining them. I don't mean to minimize the difficulties faced by authors, publishers, and readers, but I believe that some historically informed reflection could dispel the misconceptions that prevent us from making the most of "the information age"—if we must call it that.

Assignments

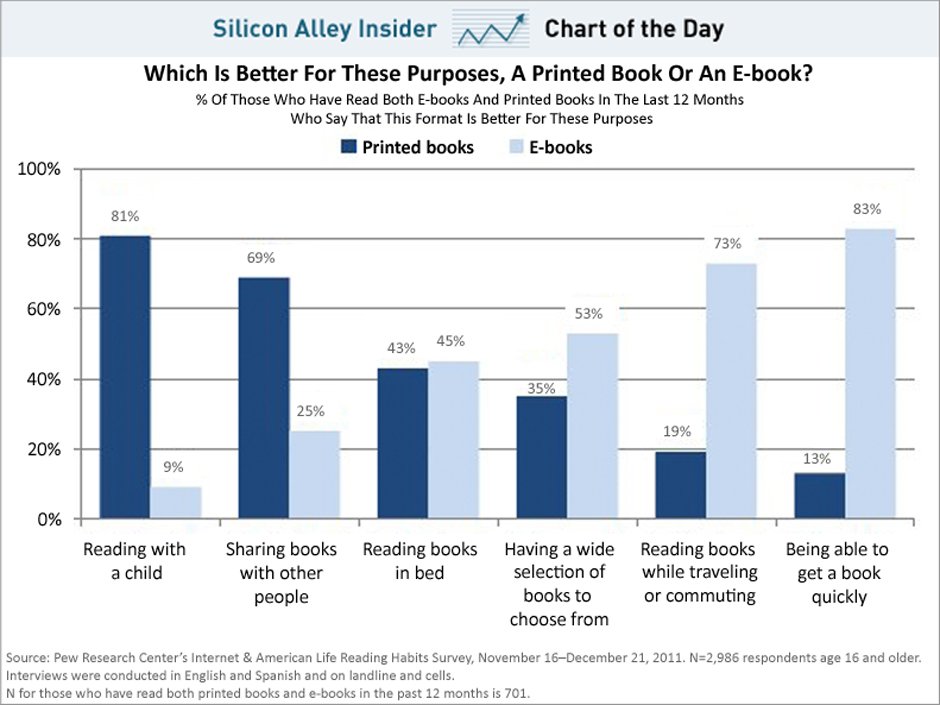

1. Do you think e-books will replace printed books? Why? Why not?

2. Do you think the Information Age has always existed or we have just entered it?

3. Do you agree that all information is available online now?

4. Why do digital texts degrade far more easily than words printed on paper?

5. Which new functions do libraries fulfill?

6. Why may the online version of the vanity press contribute to the information overload?

7. Do you agree with the author that some historically informed reflection could dispel the misconceptions that prevent us from making the most of "the Information Age"?

8. Comment the following statement:

· In 10, 20, or 50 years, the information environment will be overwhelmingly digital, but the prevalence of electronic communication does not mean that printed material will cease to be important.

9. Describe the figure below.

Fig. 1.3 Printed books vs. E-books

10. Summarize the text.

Text 4